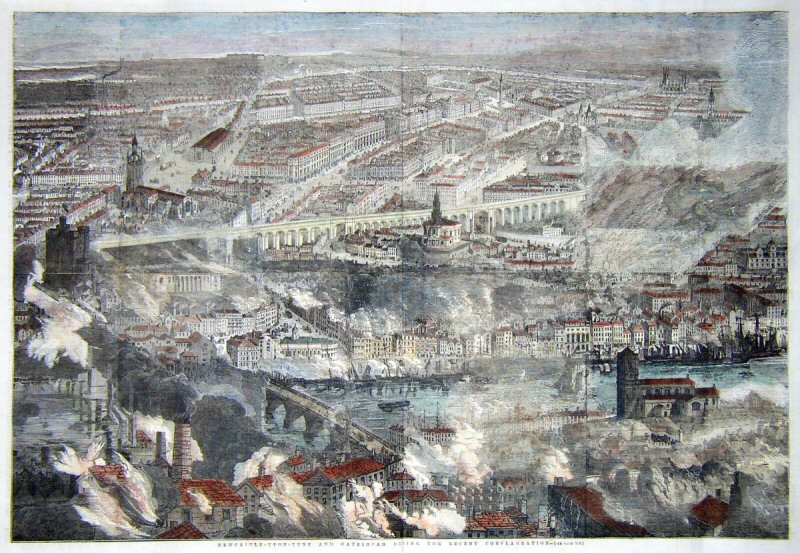

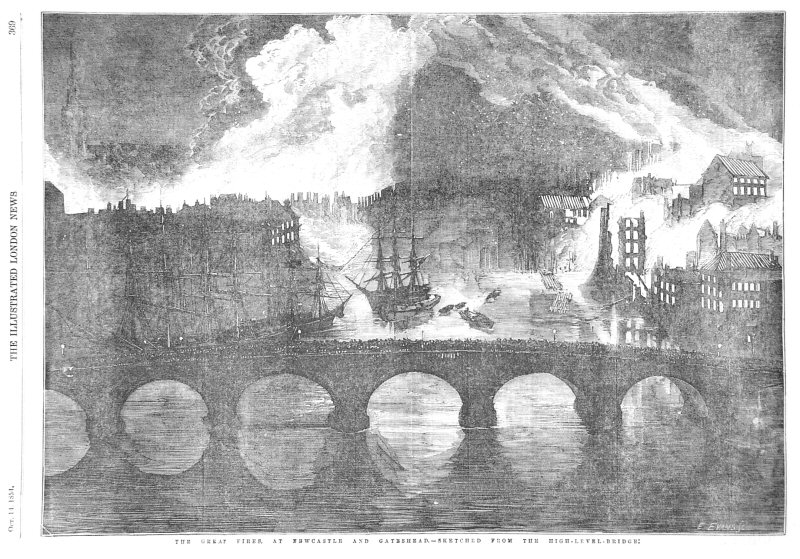

On the morning of Friday, the 6th inst., between twelve and one o’clock, a fire broke out in the worsted manufactory of Messrs. Wilson and Sons, in Hillgate, Gateshead. After raging with great fury for about two hours, the roof fell in, and the heat became so intense that it melted the sulphur which had been stored in an adjoining bonded warehouse. It came out in torrents, like streams of lava; and, as it met the external air, began to blaze: its combustion illumining the river and its shipping, the Tyne, the High Level Bridge, and the church steeples of Newcastle–spreading over every object its lurid and purple light. The flames towered far above the masts of the ships moored at the neighbouring quays. From the various floors of the warehouse huge masses of melted tallow and lead flowed in copious streams. The eight storied edifice was one mass of flame, and from every landing melted sulphur and tallow and fused lead were descending in luminous showers. It resembled a cataract on fire. At length the walls fell. Burning brands were then scattered over the roofs of the adjoining houses, had widely extended the conflagration. The ships were taken from their moorings and placed in safety. A few smart explosions were now heard, but no suspicion was entertained of the astounding catastrophe which was about to ensue.

In the immediate neighbourhood of the fire was another bonded warehouse, filled with the most combustible materials–naptha, nitrate of soda, and potash, as well as immense quantities of tallow and sulphur; and it is also said that a large quantity of gunpowder was contained in it. To this building all eyes were directed, because, although a “double fire-proof” structure, and supported on metal pillars and floors, it seemed impossible to prevent the flames from communicating with the dangerous materials within its walls. These fears were well founded. No sooner had the flames reached this compound, which was in fact nothing but a huge fulminating mixture, than an explosion took place, which no pen can describe, and which made Newcastle and Gateshead shake to their foundations. The bridge shook as if it would fall to pieces, and the surface of the river was suddenly agitated as if by a storm. The shock was felt in every street. The front doors of many private persons’ dwellings were violently opened; and the shutters of the shops, particularly towards the quay, were shaken from their fastenings, and strewed about the pavement. Broken glass was under your foot at every step. Every family was suddenly aroused, and their various members rushed together or into the streets to inquire the cause of so frightful an explosion. The sight was best witnessed from the High Level Bridge, which was crowded at the moment with anxious spectators. Suddenly as the explosion took place, that triumph of engineering skill began to vibrate like a piece of thin wire, and the first thought of those upon it was, that that magnificent erection was about to fall. The projection of the flaming materials across the river was a wonderful sight for those who had coolness enough to witness it, but there were very few in that condition. A universal stupor seems rather to have prevailed everywhere, first broken by the screams and wailings of women and children, and by the ignition of the houses on the Newcastle side of the river. It was some time, however, before the minds of the spectators awoke to the full extent of the calamity.

The shock of the tremendous explosion was felt over the whole eastern seaboard, from Blyth, in Northumberland, to Seaham, six miles to the south of Sunderland. The concussion shook all the buildings in the large manufactories on the shores of the Tyne between Newcastle and Shields, extinguished the lights, and caused the greatest alarm to the workmen, who rushed into the open air in terror and excitement. In the seaports of Shields, nine miles off, it produced all the results of an earthquake, rocking the houses, “thudding” against the doors, shaking the windows, and causing the inmates to jump out of bed in alarm and astonishment. In detached dwellings and lone farmhouses the watchdogs commenced a violent barking and noise, which, with the concussion and shaking of the doors and windows, produced an impression that an attack was contemplated by burglars. In the pit villages the impression was that an explosion had taken place in the bowels of the earth. Papers and books, partially burnt, were picked up in the fields at the Fellgate, near the Brockley-whins railway-station six miles off; and a master of a sailing vessel, on his passage to the Tyne, felt the shock ten miles off at sea.

The streets in the neighbourhood of the explosion presented a most melancholy spectacle. Men, women, and children in their night dresses might be seen rushing from their abodes in search of shelter, they knew not whither. In Gateshead particularly the scene was most distressing–mothers were vainly trying to return for a child, forgotten in the suddenness of escape–and children were searching for their parents. The quay on the Newcastle side of the river was literally strewed with burning staves and rafters, covered with sulphur, and burning like matches. Adults and children, confused by the awful catastrophe, went staggering to and fro as if intoxicated, uttering lamentable and piercing cries. At one time the whole town seemed to be devoted to the rampant agency of fire. It passed with the greatest facility from house to house. Some houses were left gutted, whilst others were almost levelled with the ground. The cracking timber of the old houses, and the noise of the falling of gable-ends and stacks of chimneys, proclaimed its progress. The tenements of the poor who lived in the vicinity of the warehouses, fell like houses built of cards, and, in some cases, it is said, buried their inmates in the ruins. All the houses in Church-walk, and Cannon-street, Gateshead, have been either partially or wholly destroyed, amounting to nearly fifty. About fifty soldiers from the garrison were advancing with the fire-engine, when the explosion met them, killing two and wounding thirty out of the remainder. Mr. Robert Pattinson, a member of the Newcastle Corporation, an active gentleman, who had sallied out to witness the fire, was suffocated by the fumes, as was Lieutenant Paynter and eight other persons–including Mr. Davidson, jun. (miller); a barber, named Hamilton; a sergeant of the Cameronians; Scott, a Gateshead policeman: the rest so burnt and mutilated as scarcely to be recognised. Mr. Davidson, father of the young man who is killed, and who owned a neighbouring steam-mill, has lost his eyesight.

Numbers of policemen on duty were severely injured by the falling débris. Mr. Ralph Little, an inspector, had one of his legs broken and several of his ribs fractured. The surgery of Mr. Rayne, surgeon to the force, was literally besieged by the sufferers. The infirmary was crowded at an early hour. Fully fifty in-door patients were received, and more than double that number had their wounds dressed. Mr. Craster, of the Gateshead Dispensary, was called to upwards of 100 cases, and most of the surgeons in Newcastle and Gateshead were attending sufferers at their own houses. Altogether, not less than 500 persons were more or less injured by the explosion. The total number of lives lost is not yet known, as many persons are said to have been buried in the ruins. Twelve bodies have been identified.

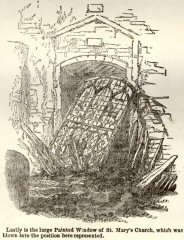

The loss of property is very great; some estimates say upwards of £1,000,000. The interior of St. Mary’s Church, Gateshead, is a ruin. Many of the grave-stones in the church-yard were removed by the force of the explosion, and thrown to a considerable distance, knocking in the walls of some of the adjoining houses. There is scarcely a house, office, or public building, within a radius of a hundred yards of the explosion, which has not been injured–either unroofed, or its windows broken. The flames spread with great rapidity; and special engines were dispatched from the central station to bring the fire-engines from Hexham, Sunderland, Shields, and other towns. There was, happily, no want of water, the Tyne being so close at hand; and the water of the Whittle Dean Company, which is always at a high pressure, was served with admirable effect on the flames, which were not thoroughly subdued, however, for some days.

In Gateshead, the entire mass of buildings–extending several hundred yards–from Bridge-street and Church-street, eastward, and from Church-walk to the river, is entirely consumed. Church-walk was hardly passable; and Hillgate was completely choked up with the ruins. On the Newcastle side the devastation is frightful. Along the Quay, and towards the head of Butcher-bank, the thoroughfare was blocked up on Saturday by the heaps of rubbish, and the danger of dilapidated property falling in the streets. From the corner of the Sand-hill to within a house or two of the Custom-house–or half the length of the Quay–the property extending backwards, including shops and offices in front, and warehouses behind, lay a mass of calcined ruins.

An inquest has been held on the bodies, eleven in number, which, up to Saturday morning, had been extricated from the ruins on the south side of the river; but no clue has yet been obtained as to the cause of the explosion. The inquiries were principally directed to the point whether gunpowder was stored in or about the bonded warehouses. Mr. T. Lange said they never had, to his knowledge, any gunpowder stored there; though it would be possible for some to be there without his knowledge, as the warehouseman had a key. Other occupiers of the premises gave similar evidence, and put in lists of goods in their respective stores. Some of the witnesses thought the explosion had been caused by the nitrate of soda, of which there were large quantities in the bonding warehouse.

In consequence of a communication from the Mayor and Corporation of Newcastle, on behalf of the inhabitants, requesting the aid of a Government officer in the enquiry, the Secretary of State has directed Captain Ducane, of the Ordnance, to be present, and to assist in the investigation. The storing of any large amount of gunpowder in an inhabited town is clearly against the law, and exposes the transgressors to heavy penalties. However, in this case it may turn out that the distressing casualty might have been caused by explosive materials not in a perfectly manufactured state. In the face of such an appalling calamity, however, the strictest investigation is considered necessary.

On Tuesday morning a meeting of the representatives of the various fire insurance companies having offices or agencies in the town, was convened in the Central Exchange Hotel, in order to adopt the best measures for ascertaining the losses sustained by the late calamitous fire, and for carrying out all necessary proceedings connected with the same; W. Woods, Esq., of the Newcastle Fire office, in the chair. The following were appointed to a committee to enter into the necessary details:–namely, the agents, respectively, of the Newcastle, the Phœnix, the Sun, the Royal Exchange, the County, the Manchester, the Leeds and Yorkshire, the North British, the Norwich Union, and the Anchor offices; five to be a quorum, and Mr. Woods to be convener. Resolutions to the effect that the committee be authorised to take such steps as may be considered judicious to investigate the cause of the explosion; and that they endeavour to estimate the loss of life and injury sustained by those who had suffered in the discharge of their duty, were severally put from the chair, and unanimously adopted.

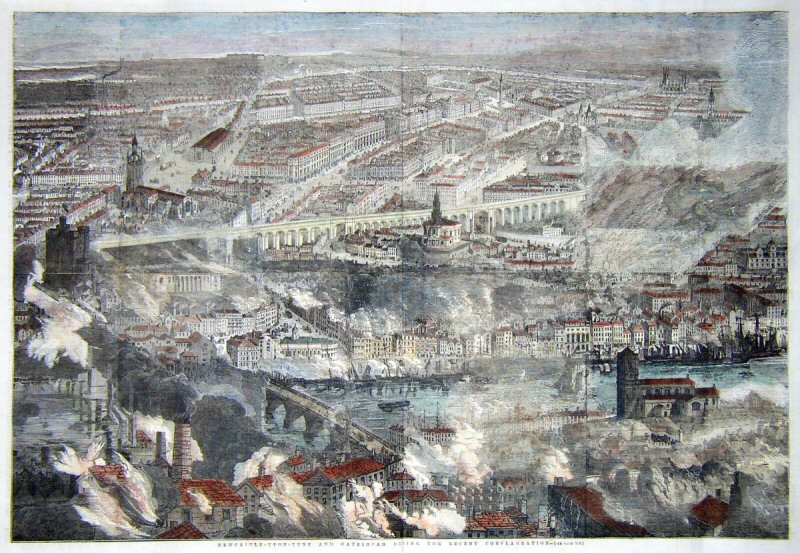

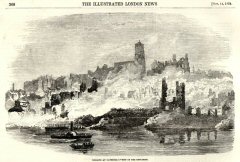

The Ruins of the Bonded Warehouse at Gateshead - the site of the explosion, with St. Mary's Church in the background

A View in Gateshead

The large painted window of St Mary's Church, which was blown into the position here represented

The most terrible and appalling catastrophe which ever occurred in the towns of Newcastle and Gateshead took place at an early hour this morning, under the following circumstances:— Shortly before one o’clock a fire was discovered in the worsted manufactory of Messrs. J. Wilson and Sons, fronting the river, and situate in Hillgate, Gateshead, a building which had only recently arisen upon the site of a fire which took place on the 9th of October, 1850. The manufactory, which was of considerable height, was stored with wool in various stages of manufacture, and contained, also, a quantity oil, &c., and the inflammability of these articles offered such food to the flames that in less than an hour the building was entirely gutted from roof to cellar. On the east side of Messrs. Wilson’s manufactory stood a warehouse, about a 100 yards in length by 18 in breadth, originally built for storing goods by Messrs. Bertram and Spencer, and had been used as a free warehouse for the storage of merchandise. At the time of the fire it was stored with 200 tons of iron, 800 tons of lead, 170 tons of manganese, 130 tons of nitrate of soda, 3000 tons of brimstone, 400 tons of guano, 10 tons of alum, 5 tons of arsenic, 30 tons of copperas, 1½ tons of naptha, and 240 tons of salt.

The intense heat from the manufactory placed this building in great jeopardy, and streams of vivid blue flame proceeding from the sulphur soon poured from the doors upon the various flats, and afforded a most extraordinary spectacle. The most strenuous efforts were made by the fireman, as well as by the soldiers of the 26th Regiment, but perfectly in vain, and by three o’clock the whole range was one immense sheet of fire. The alarm had by this time spread in every direction, and had attracted a large number of the inhabitants of both towns to the scene. The Quayside, Newcastle, affording a full view of the burning property, was deeply set with spectators, but not the slightest apprehension was felt of any outbreak in Newcastle, and the crowd was fortunately much smaller than it would otherwise have been; but in Gateshead, where the dwellings of many thousand persons were in close proximity to the flames, and the alarm was naturally intense, every spot was thickly studded with spectators.

At about ten minutes past three a slight report, like that of a rifle, was heard, but it occasioned no movement, and was thought merely accidental; but about three minutes after it was followed by an awful explosion, which rocked with a fearful sound the whole town to its foundations, and which no description can give the slightest idea of. The burning piles of brimstone, with bricks, stones, metal, and articles of every description were thrown up with the force of a volcanic eruption, only to fall with corresponding momentum upon the dense masses of the people assembled, and upon all the surrounding habitations. The crowd upon the Quayside and Sandhill was mown down as if by a discharge of artillery, many being rendered insensible from the shock, others temporarily suffocated by the vapour, and many more wounded by the flying debris. An awful calm succeeded for a few seconds, and then, as most of the sufferers regained their consciousness, an appalling wail of distress arose in all directions, but many were far removed from all earthly suffering, and their voices were never heard again.

The fearful extent of the calamity was now perceptible. The ignited missiles had penetrated into three houses upon the Quayside, standing exactly opposite the fire, to such a prodigious extent, that they were in flames in every storey in less than five minutes. The ships lying in the river were nearly blown out of the water by the concussion, and their shrouds were set on fire by the projectiles. Many scores of houses were entirely unroofed, the descending rubbish doing fearful injury. The shop fronts and windows upon the Quayside, the Sandhill, the Side, and all the neighbouring streets, were almost universally blown out, and the gas lights, for a square mile around the spot, were extinguished in a moment, adding a weird and horrible confusion to the scene. The streets rapidly filled with the entire population of the lower parts of Newcastle, hundreds of them in their night clothes, and seriously injured. The blood-begrimed countenances of many, and the shrieks, wailing, and lamentations to be heard on every side, commingling with the voices of others devoutly calling upon the Lord to have mercy upon them, made up a scene which has been seldom paralleled.

As the uninjured regained their presence of mind every endeavour was made to render relief to the wounded. The latter were at first laid on the pavement round the Fish Market, in the most melancholy confusion, and afterwards removed to the Infirmary, and never were the resources of that great charity so severely tried. Fifty-eight persons, seriously injured, were immediately admitted into the hospital, fifteen of whom died there, and sixty-three others were relieved as “out patients.” Such were the first effects of the calamity in Newcastle, but the worst remains to be told. The long and narrow street in Gateshead, called Hillgate, where the fire broke out, was filled with people at the time of the explosion, the firemen, the police, and various assistants being within a dozen yards of the burning pile.

A number of influential inhabitants were also present, rendering every assistance in their power, and amongst them were:—Mr. Robert Pattison, tanner, a member of the Newcastle Council; Mr. Charles Bertram, a magistrate of Gateshead; Mr. Henry Harrison, basket-maker; Mr. William Davidson, son of Mr. Davidson, miller, (whose extensive premises were within a few feet of the fire, and were afterwards consumed) ; Mr. Alex Dobson, son of John Dobson, esq, architect; Mr. Thomas Sharp, a gentleman of independent means; and several others. In this narrow gorge the burning rubbish fell in tons together, burying the gentlemen we have named, together with Ensign Paynter—who was at the head of a company of the 26th Regiment in Church Walk—and many others several feet deep. Of course their death under such circumstances must have been instantaneous. Others, again, were suffocated by the deadly fumes, while a third section perished by the falling of the surrounding houses which were thrown into one mass of ruins. Whether the loss of life was accurately obtained at the time is yet a matter of opinion, but the total number known to have perished was no less than fifty-three

Of course the explosion greatly increased the extent of the fire in Gateshead. The vinegar works of Messrs. Singers and Co., which adjoined the warehouse, soon fell a prey to the flames; the fellmongery of Messrs. Wilson was also burnt down, and several private dwellings shared the same fate. But on the Newcastle side of the river the destruction was more awful and alarming still. It has already been said that the fire broke out in three houses opposite the warehouse in Gateshead. The shops on the ground floors of these premises were occupied by Messrs. Smith and Co.. drapers; Messrs. Ormston and Smith, stationers; and Mr. Harbottle, draper, and the stock in all was valuable. Besides these premises the shop of Messrs, Spencer and Son, drapers, and the offices above (one of which was occupied by Mr. Bertram whose death has just been recorded) were almost entirely reduced to ruins, by stones projected from the site of the explosion. The property immediately behind Messrs. Ormston and Smith’s, was the Dun Cow, in the occupation of Mr. Teasdale, and the spirits which it contained immediately gave increased energy to the flames, which consumed the whole fabric in less than half-an-hour.

The fire then gradually progressed both north and east, making its way in the first direction up Grinding-chare, principally through old warehouses, toward the Butcher-bank; and in the second, along the range of buildings on the Quayside. The shops of Mr. Aikin, bookseller, Mr. Turnbull, watchmaker, and the Grey Horse Inn, succeeded Messrs. Smith and Co., and the flames again ran north, up Blue Anchor-chare and Pallister’s chare towards the Butcher-bank, and again extended along the Quayside. The shops of Mr. Snowdon, grocer, and the Sun Inn, intervened between Pallister’s chare and Peppercorn-chare, where the flames made another run to the north of Colvin’s-chare and Hornsby’s-chare. By six o’clock the fire had spread along the Quayside for nearly one hundred and twenty yards, while the extent of the fire towards the Butcher-bank was rather greater, it having travelled up the whole length of Blue Anchor-chare, Peppercorn-chare, Pallister’s-chare, and Hornaby’s-chare, and made a breach into the Butcher-bank by three separate houses, all of which were entirely consumed. All this time a third fire was raging. At the time of the explosion a large blazing beam of timber was thrown high over the Butcher-bank and fell into the workshops of Mr. J. Edgar, situate behind his premises in Pilgrim-street. Here the flames worked their way uncontrolled, destroying a front shop occupied by Mrs. Ann Shield, grocer, on one side, and a large number of tenemented dwellings and workshops adjoining the George’s-stairs on the other.

By this time the sun had risen, and never, perhaps, had his rays exhibited Newcastle in so awful a state. The fire was still extending widely amongst the property near the Quayside, whilst the flames in Gateshead were quite unsubdued. Owing to the fire-engines having been almost entirely buried in the ruins and the serious injuries that had been sustained by the firemen, there were no adequate means available for checking the progress of the flames. The engine of the North-Eastern Railway Company was fortunately uninjured and proved of great service on the Quayside. Communications were sent by telegraph to all the neighbouring towns for assistance in the emergency. The floating engines at Shields and Sunderland, three land engines from the latter town, and one each from Hexham, Durham, Morpeth, and Berwick, were sent by the authorities of these places by the most expeditious means available, and the supply of water from the company’s pipes continued most abundant to the last, and was exceedingly effective even when engines were not obtainable.

On the 7th the fire was got under on both sides of the river, and immediate steps were taken to disinter the bodies of those who were known to be killed by the calamity. Amongst those the bodies of Mr. Pattinson, Mr. Hamilton, hairdresser, Ensign Paynter, Corporal Stephenson, Mr. Willis, a skinner, Mr. Duke, a bricklayer, and his son, a child named Conway, and McKenny, a labourer, were rescued. On the 8th the body of Mr. Mosley, a smith, was found much disfigured; and about noon a charred and crumbling mass was discovered, without the least resemblance to humanity. A piece of the coat and a bunch of keys, lying close by, led to its identification as that of the son of John Dobson, esq. The next fragments found were those of Mr. Thomas Sharp, a gentleman, shockingly mangled, but were identified by his gold watch and two dog whistles. Several other bodies were discovered in a similar condition. Mr. Davidson was identified by a signet ring, Mr. Harrison by a cigar case, one of the fireman by the nozzle of the engine pipe, and many others by similar articles known to have belonged to them. In Church-walk were found the family of a man, named Hart, consisting of himself, his wife, his son, and his niece. No portion of Mr. Bertram’s body could be found, but a key, which he was known to have, and his snuff box were discovered among the ruins.

Inquests were soon after opened on the bodies, and a great amount of evidence was tendered as to the cause of the explosion, the general opinion being, that nothing but a vast store of gunpowder could have been the cause of the catastrophe. Mr. Hugh Lee Pattinson offered an explanation of the disaster, which he attributed to water, whilst Professor Taylor suggested the probability of its origin to gas. Mr. Pattinson believed that the heat of the building had inflamed the sulphur, and, gradually, the whole mass of nitrate of soda and sulphur in the lower vaults had melted together, producing intense combustion and a heat such as could not well be conceived, and his assumption was, that whilst in that state, a body of water had found its way to the burning mass, and, by the immense expansive power of steam at such a heat, had caused the explosion. In his opinion 328 gallons of water falling in this way, would have as powerful an effect as eight tons of gunpowder. Professor Taylor supposed, that the sulphur having taken fire had inflamed the nitrate of soda, which he said, would set free half-a-million cubic feet of gas, and the inability of the gas to escape fast enough through the door of the vault, had, he believed, caused the explosion. Both chemists, from various analysis of the ruins, were equally confident that no gunpowder had been present. The juries, after very lengthened sittings, finally came to open verdicts, expressing, however their belief that the explosion had not arisen from gunpowder. The loss by this terrible fire was never accurately ascertained, but it was pretty generally estimated at half a-million.

In Newcastle, commencing at the east end of the property destroyed upon the Quayside, the following is a list of the principal sufferers:—Mr. G. Wilson, eating-house keeper; Mr. C. M. Mowbray, ironmonger; Free Porters’ Office greatly damaged; Messrs. A. Parker and Co.; Mr. G. Buckum, sailmaker; Mr. James Wilkin, broker; Messrs. E. Liddell and Co. ; Mr. M. Plues, merchant; Mr. George Grey, broker; Messrs. Featherstone and Elder, ship chandlers; Mr. S. Bailey, watch maker; Mr. J. Potts, broker; Mr. D. W. Hay, baker; Messrs. Carr and Barras, brokers; Mrs. Swallow, Rising Sun; Mr. L. Reed, chemist; Mr. G. Brown, butcher; Mr. W. Wilson, cooper; Mr. W. Berkley, malster; Mr. Mark Thompson, ship chandler; Mr. W. J. Van Haansbergen, merchant; Mr. J. Ormston, wharfinger; Messrs. J. Carr and Co., coke manufacturers; Messrs, C. Lotinga and Co., brokers; Mr. David Don, spirit merchant; Messrs. Longridge and Co., merchants; Messrs. John Rogerson and Co., brokers; Messrs. Joseph Cowen and Co., fire brick manufactnrers; Mr. Charles West, broker; Mr. George Wraith, broker; Mr. Henry F. Morrison, sailmaker; Mr. T. Guthrie, sailmaker; Mr. T. F. Davidson, Sun Inn; Mr. John Snowdon, grocer; Messrs. S. M. Frost and Co., cartmen; Messrs. T. L. Colbeck and Co.; Mr. Thomas Dixon, Prussian Arms; Mr. A. Naylor, hair dresser; Mr. W. Atkin, bookseller; Mr. Hans. Peter Mork, merchant; Netherton Coal Company; Mr. S. D. Gething; Mr. G. P. Birkinshaw; Mr. G. Robertson, sailmaker; Messrs. Leidemann and Co., brokers; Messrs. R. Thiedemann and Co., brokers; Mr. James Harding, Grey Horse Inn; Mr. Fairweather, watch-maker; Messrs. Macky and Smith, drapers; Broomhill Colliery Office; Mr. Fisher, fruiterer; Messrs. Ormston and Smith; Mr. James Scott, broker; Messrs. Alexander and Wood, provision merchants; Messrs. Charlton and Angus, commission agents; Mr. Wm. Teasdale, Dun Cow; Mr. Batey, Golden Anchor; Mr. Jules Averauw, broker; Mr. John Harbottle, draper. Butcher-bank— Mr. Isaac Temple, paper merchant, house and shop completely destroyed; Mr. Piper’s furniture shop and workshops behind shared the same fate; Mrs. Bailes, grocer, shop entirely consumed. Pilgrim-street—Mrs. Shield, grocer, house and shop burnt to the ground; Mr. J. Edgar’s workshops entirely destroyed; a great number of small tenemented houses and workshops burnt down.

In Gateshead the premises of different kinds totally destroyed were as follows :—Mr, Bulcraig’s engineering works; Messrs. J. T. Carr and Co.’s timber yard, with tenemented houses behind; Mr. Wilson’s worsted manufactory; Mr. Bertram’s warehouse; Mr. Singers’ vinegar manufactory; Mr. Davidson’s extensive flour mill; Mr. M. Dunn’s beer shop; a number of tenemented houses and small shops in Hillgate; Mr. Wilson’s fellmongery; Mr. Martin Dunn’s timber yard. Church-walk was almost entirely demolished, and many other houses it is impossible to enumerate. The public sympathy for the numerous poor families, who were rendered destitute by this terrible catastrophe, was displayed in the most marked manner throughout the kingdom. Upwards of £11,000 were subscribed for their relief. No less than eight hundred families applied for assistance from the funds, and, altogether £4,640 were paid for the loss of furniture. In February, 1857, the committee stated that they had expended £6,533, and reserved £3,044 for widows and orphans, and the remainder of the funds was distributed as follows:—Newcastle Infirmary, £1,190; Gateshead Dispensary, £314; Ragged Schools, £195; other charities, &c.. £50.